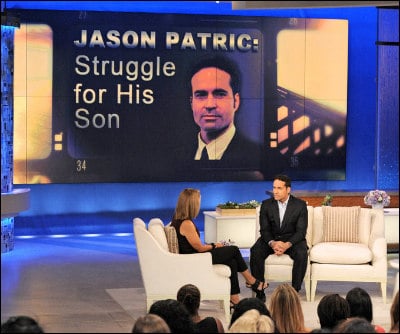

Actor Jason Patric has a case in the California courts that has gained national media attention recently because it involves the paternity rights of sperm donors. Patric’s child was conceived by his former girlfriend through in vitro fertilization using Patric’s sperm. Now he’s fighting to be declared the legal father of that child and to have custody and visitation rights established.

Actor Jason Patric has a case in the California courts that has gained national media attention recently because it involves the paternity rights of sperm donors. Patric’s child was conceived by his former girlfriend through in vitro fertilization using Patric’s sperm. Now he’s fighting to be declared the legal father of that child and to have custody and visitation rights established.

In 2013, the Virginia Supreme Court decided a similar case involving assisted conception: L. F. v. Breit, 285 Va. 163; 736 S. E. 2d 711. The biological father in that case, William Breit, was also seeking to have paternity established, as well as custody and visitation rights, for a child that was conceived via in vitro fertilization using his sperm. Unlike the California parties, William Breit and his long time, live-in girlfriend entered into a written custody and visitation agreement, prior to the child’s birth, that gave Breit reasonable visitation rights. After the child’s birth, they both signed a sworn affidavit of paternity stating that Breit was the legal and biological father, and his name was put on the birth certificate. Four months after the child’s birth, the couple separated, but Breit continued to visit and provide for the child. Nine months after they split, the child’s mother ended all contact between Breit and the child.

The issue before the Court in L. F. v. Breit was whether Virginia statutes prevented an unmarried, biological father from establishing legal parentage of a child born as a result of assisted conception, pursuant to a voluntary written agreement. After a thorough analysis of the parties’ arguments and the applicable state and federal laws, the Court concluded that Mr. Breit was entitled to establish paternity with a written acknowledgement of paternity, pursuant to Virginia Code Section 20-49.1, despite the statutory presumption set out in Virginia Code Section 20-158 that an unmarried sperm donor is not a parent. The Court found that because Mr. Breit had demonstrated a commitment to his parental responsibilities, the Due Process Clause of the U. S. Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment protected his fundamental right to make decisions concerning the care and custody of his child.

In May 2014, the Circuit Court in Roanoke issued an opinion in another unmarried sperm donor case, but one with a different twist: Boardwine v. Bruce (VLW 014-8-053). Robert Boardwine (“Robert”) and Joyce Bruce (“Joyce”) had known each other since the 1980s—but had never been romantically involved. In 1999, Joyce asked Robert if he would donate his sperm to her so that she and her partner could have a baby. He declined, indicating that if he was going to donate his sperm, he wanted to be involved as the child’s father and he didn’t think he was ready for that responsibility at the time. In 2010, she asked him again and this time he agreed.

Joyce inseminated herself at home, using Robert’s sperm and a turkey baster. After several attempts, she conceived a child. About four months into the pregnancy, the parties had a falling out over the choice of names for the child and thereafter had little contact until the birth. Although they had discussed a written agreement outlining Robert’s parental rights, they never signed one.

Nevertheless, Robert believed that he and Joyce had an understanding and were in agreement that he would have rights as the child’s father. However, Joyce would later claim that she only agreed to informal contact with the child, not formal custody and visitation. A DNA test confirmed, with a 99.9% probability, that Robert is the child’s biological father.

In deciding this case, the court had to analyze and harmonize several sections of the Virginia Code. Section 20-158 states that a donor is not the parent of a child conceived through assisted conception, unless the donor is the husband of the woman who gave birth to the child. Assisted conception is statutorily defined as a pregnancy resulting from any intervening medical technology that completely or partially replaces sexual intercourse as the means of conception. The court ruled that Joyce’s self-insemination with a turkey baster was not an intervening medical technology because it did not involve the assistance of a physician. Therefore Section 20-158 didn’t apply, and Robert could establish paternity based on reliable genetic testing indicating a 98% probability of paternity, pursuant to Virginia Code Section 20-49.1. But, even if Section 20-158 did apply, it wouldn’t have prevented Robert from establishing paternity because, in addition to the DNA test, he had clear and convincing evidence that the parties intended for him to be the child’s legal father.

While the Virginia Supreme Court in L. F. v. Breit cleared a path for sperm donors to establish paternity, some obstacles may remain. The facts of each individual case are extremely important. If you are interested in participating in any form of assisted conception, be sure to consult with an attorney. If you are a resident of Northern Virginia, the experienced family law attorneys at Livesay & Myers can help. Contact us to schedule a consult today.